| brucekluger.com |

USA Today, September 12, 2002 Children can conquer their fears By Bruce Kluger I was sitting on a lawn chair in my in-laws' backyard in Cleveland, enjoying the sun during a brief family getaway from New York City. I glanced over at my daughters— Bridgette, 7, and Audrey, 3—and watched with growing curiosity as they began playing a game they'd just made up. First, Audrey stood upright, legs and arms extended like a tiny scarecrow. Then Bridgette began tracing the outline of her little sister's body with a toy flute, head to toe, front to back. As peculiar as this pantomime was, I instantly recognized what my daughters were recreating: airport-security procedures. We'd

fascination as they watched passengers going through the now-familiar routine of electronic body scanning.

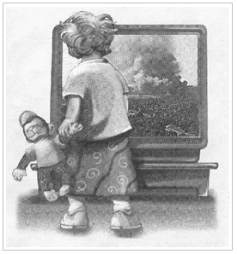

queasy. In fact, for the first time since Sept. 11, 2001, I understood that they were going to be OK. With this week's one-year anniversary of the terrorist attacks, attention is once again focusing on the nation's children. Columnists and commentators continue to ponder the legacy we leave them while offering up sundry prescriptions for helping them to cope. As a father (and an American), I'm not convinced all of this hand-wringing is necessary. Even as we grownups pinwheel through this turbulent time, tying ourselves into knots over how to gently escort our kids through the emotional rubble of 9/11, children have a remarkable way of navigating their own routes to safety, whether they're holding our hands or not. Just look at the numbers: Of 1,100 students ages 8-18 recently polled by the Harris Interactive marketing group, only 8% fear they will become victims of terrorism, while a healthy 83% are confident they will live long enough to achieve their dreams. Pretty good news, given a pretty bad year. How have so many children maintained balance while the adults in their lives still stumble with worry? As any parent can tell you, kids specialize in ricocheting from the linear to the abstract, from the rational to the hysterical. When it comes to perceiving the world around them, they operate on two levels, dutifully absorbing their parents' concepts of "good" and "bad" and "do" and "don't" while simultaneously conjuring their own perspectives on the images and events bombarding them. Although childhood experts have recommended an endless variety of often thoughtful, hands-on approaches to helping our kids deal with post-9/11 anxiety— from encouraging them to talk at length about their feelings to proposing they draw pictures of planes colliding with towers—children also need the time to confront their fears alone. We should give them that privacy. This is not abandonment; it's parenting. As Selma Fraiberg pointed out in her landmark 1959 study of children, The Magic Years, kids whose parents don't permit them to be shaken by life's bumpier passages "are deprived of an important means for preparing for danger: anticipatory anxiety." In other words, Fraiberg says, by allowing our children to exercise their glorious imaginations—even if those imaginations take them down some pretty dark roads— we may just be helping them learn to douse those fears the next time something bad happens. Case in point: As the twin towers were crumbling, my wife and I brought Bridgette home from school early. We immediately permitted her to join the small group of friends and family at the TV—two of whom had only an hour before fled Lower Manhattan as the buildings burned—preferring to walk her through the images she would undoubtedly see countless times in the days to come. Bridgette silently stared at the wrenching replays of the air assaults on the towers for a few minutes before wandering off to watch I Love Lucy videos in our bedroom. Ordinarily a child who craves her parents' company, Bridgette didn't emerge for two hours. Her message was loud and clear: "I don't like what's going on in the living room," she was telegraphing. "I think I'll let you grownups handle this stuff." Sure enough, during the next few weeks the questions slowly began emerging, particularly about the safety of her mom, who works in the Empire State Building. In the end, Bridgette achieved "closure" by absorbing the events of 9/11 in her own way, in her own good time. During the past year, I've watched dozens of kids adopt the same strategy in the simple laboratory of my daughters' peer group. Five-year-old Hannah made commemorative bracelets from blue and green threads (to represent the Earth), then distributed them to everyone she knew; a neighborhood boy insisted his grandfather "fell off the roof" of the World Trade Center, a completely fabricated story he kept repeating until he got it out of his system; another boy made endless towers of Legos, knocking them down again and again until he was nearly exhausted. Even my 3-year-old, bless her heart, found a clever, if not comical, solution to the household tension she sensed in the weeks following 9/11. Audrey had just begun enjoying storybooks around the time the terrorist attacks occurred. Thanks to all the grownup chatter buzzing about her head, she somehow came to the conclusion that Curious George and George Bush were one and the same. Naturally, a preschooler hasn't the foggiest notion about the geopolitical state of the world, but I'm convinced that Audrey's merging of the two Georges was no accident. Only a child could find the comfort zone with such divine simplicity. As we look beyond this week's anniversary and contemplate the ways we can help our children face an uncertain future, perhaps we can take consolation in the fact that, not so long ago, we were pretty resilient kids ourselves. Many of us were only in grade school when the nation convulsed over the murder of President Kennedy, yet we managed to pull through it all OK—without the help of grief counselors or study guides or two-hour televised town meetings. Indeed, it was only 11 weeks after the assassination that American youth found new heroes to turn to simply by flipping on The Ed Sullivan Show one Sunday evening to watch four lads from Liverpool strum guitars and shake their heads. We had found our solace—someone who wanted to hold our hand. (Illustration by Web Bryant, USA TODAY) |